BY MART-MARIÉ SERFONTEIN

The corner on lower Victoria Street, next to Die Mystic Boer, looks a little different. Where students and residents of Stellenbosch were once used to seeing an old structure standing vacant, frequently with a few vagrants sleeping on the porch, now stands a newly renovated building that has been painted, plastered, and has tables and chairs outside.

What used to be the old clinic, later left unused by the municipality, is now the CoCreate Hub, run by the non-profit urban planning consultancy, Ranyaka. It is a space for local entrepreneurs to exhibit and sell their locally-made wares and products, and also has a sit-down area with a local barista serving coffee, as well as food vendors selling street food-style meals.

Marli Goussard, an Enterprise Development Manager for Ranyaka, who is involved with the CoCreate Hub programme, explains that the non-profit is a “town planning social enterprise, started by Johan Olivier in 2010, with the purpose of implementing collaborative community transformation within a community geographically.”

Ranyaka tries to pinpoint and understand the needs within a specific community and, based on a number of factors, then runs programmes that seek to address those needs. The CoCreate Hub is one such example of a programme that is run based on the needs within the Stellenbosch community—especially on the economic inclusion of areas geographically outside of central Stellenbosch, as well as on the social inclusion and cohesion between people from different areas that make up the greater Stellenbosch area.

As Sonya Olivier, Ranyaka’s Marketing Manager, puts it, “everyone working here, those selling their products and those coming in, would never have come into contact with each other if this Hub didn’t bring them together.”

The Stellenbosch municipality advertised the tender for 7 Victoria Street in 2018 and Ranyaka received the contract in 2019. With the help of sponsors, renovation and rebuilding could begin over the course of last year. The sponsors include the Industrial Development Corporation, the Jannie Mouton Foundation, Nedbank, BUCO (who sponsored the building material), Entersekt, and Stellenbosch University (SU), with the money donated having come from the university’s Social Impact portfolio.

Dr Leslie van Rooi, Senior Director of Social Impact and Transformation, says that the university did not think twice about supporting the Hub. “SU responded as the Hub will focus on investing in entrepreneurs and small businesses on various levels in the greater Stellenbosch. The old clinic, now the CoCreate Hub, is on the doorstep of the Stellenbosch campus; and as such, SU, like other partners, responded to a request to help with the refurbishment of the building that, indeed, leads to the establishment of the Hub.”

Furthermore, Van Rooi says that SU truly hopes the Hub will create new economic possibilities for small businesses, and that the university can bring about shared economic growth in the town in this way.

The cost of the whole project was around R3 million and could only be realised because of the donations made.

The building that used to house the local clinic was left vacant for many years and became derelict until William Hammers, a senior technologist from Idas Valley, drew up the plans for its reconstruction and renovation; additionally, Italian architect Riccardo Panzerri, who has been a long-time Stellenbosch resident, with experience in the restoration of heritage buildings, was also called in to take part in the process. It was, however, Hammers’ responsibility to get the plans approved and legalised by Heritage Western Cape. The old clinic is not a proclaimed heritage building, but because it is older than 100 years, it is of special interest.

The original architecture of the building was preserved, with the original lintels still standing, and some parts of the wall left exposed to show the original brickwork. According to Hammers, their biggest task was in taking out the ceilings and leaving the support beams exposed. All the original beams were left and, on the recommendation of the structural engineers, a few new support beams were added and painted white, so as to be distinguished from the old beams, which were varnished and stained darker.

The only other reinforcement work done on the building was on the walls. Hammers explains that when they took the original plaster off of the brickwork, the brick crumbled away into sand and, in replastering, they had to apply a mesh between the brickwork and the new plaster, both as a support for the old bricks and as an adhesive for the plaster. All the floors were made level to ensure that the building is wheelchair-friendly.

According to Goussard, 90% of the money spent on workmanship throughout the whole process benefitted local contractors, builders, carpenters, and painters.

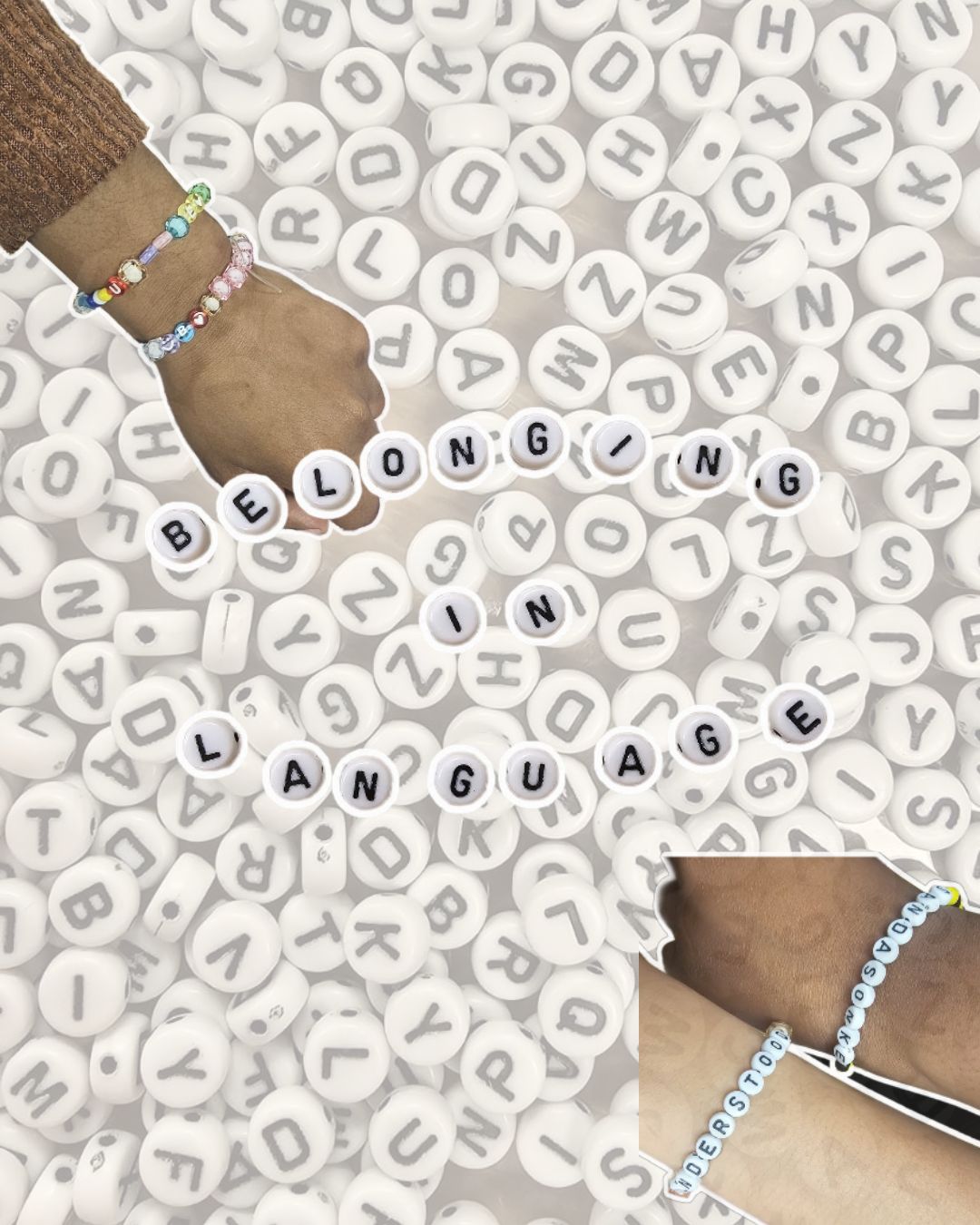

The building, as it stands today, displays many products from different entrepreneurs, from baked goods — both sweet and savoury — to braai sauces, tikka masala and spices, to leather bags and locally made jewellery. Inside, there is a room dedicated to fashion, another that houses a barber, and a coffee shop with enough space for students to have a break and chat, or simply to sit and work close to campus, while making use of the free Wi-Fi provided. Outside are the street food vendors with affordable bites to eat.